The Problematics of ‘Informal Urbanism’ as a Terminology and its Use to Refer to Palestinian Localities in Israel

Venus Ayoub

According to Habitat Universities Thematic Hub, ‘informal urbanism’ is understood as “the production of urbanization that is independent from formal frameworks and assistance (if they exist) that do not comply with official rules and regulations.” 1 Ananya Roy defines it as “a state of exception from the formal order of urbanization.” 2 The term ‘informal urbanism’ is often used by scholars as well as policy makers describing the bottom-up developments of Palestinian localities 3 in Israel, where construction of mainly residential structures do not conform with master plans. Nurit Alfasi refers to these localities as ‘informal’ in her article “Doomed to informality,” indicating that ‘informal’ urbanism is these localities’ only choice. 4 Yosef Jabareen has also used this terminology claiming that these developments are merely translations of community necessity and its right to develop its own spaces to survive. In a more recent publication, Jabareen and Switat refer to these type of developments, specifically the ones in the Naqab 5 , with the term ‘insurgent informality,’ 6 which builds on Miraftab’s notion ‘insurgent planning.’ ‘Insurgent planning' is a counter planning practice that responds to unjust hegemonic planning agendas, specifically in response to marginalizing neoliberal practices. 7 However, Jabareen and Switat broaden this view by conceptualizing ‘insurgent informality’ not only as counter planning practice to neoliberal agendas, but also to hegemonic ethnocratic policies. 8

A UN Habitat report states that ‘informal urbanism’ in literature encapsulates ‘nonplanned,’ ‘sporadic,’ ‘illegal’ and ‘unauthorized’ spaces created in a ‘spontaneous’ manner that causes a ‘threat’ to city development. 9 Yiftachel agrees on the connotation of this terminology, specifically in the Palestinian-Israeli context. He refers to ‘informal’ spaces as ‘gray’ spaces, and claims that they are associated with ‘criminality,’ ‘contamination,’ and considered a ‘danger to the desired order of things.’ 10

On the other hand, scholars like Durst and Wegmann draw attention to the fact that the binary between ‘formality’ and ‘informality’ is constructed. Their analysis of ‘informality’ is based on three definitions: informality as a non-compliant, non-enforced, or deregulated economic activity. ‘Non-compliant informality’ refers to situations where the state consciously ignores or legitimates certain informal activities, while it denounces, punishes, or eliminates others. This leads to the second category, ‘non-enforced informality,’ whereby state enforcement is selective. Lastly, ‘deregulated informality’ refers to deliberate and pre-planned informality, that does not adhere to a regulatory power in order to better distribute resources and the state willfully withdraws from regulating these informal activities. 11 These definitions imply that ‘informal’ activities are not all equally informal and are not all dealt with in the same manner. This signifies that there are certain power dynamics playing an essential role in defining what is ‘informal.’ In fact, Durst and Wegmann stress that through the case of ‘informal housing’ in the US, stating that even though informal houses are a longstanding and widespread practice, it is completely absent from domestic discussions of housing policy, very little researched, and is in fact often met with “resistance or skepticism.” 12

Despite urban informality taking different forms and occurring in different contexts, it is still mostly associated with less developed localities, urban poverty, and marginalized communities; to the extent that urban informality research is almost exclusively concentrated on the global south and fails to recognize informality in developed localities. 13 Frank I Müller contributes to this perspective by stating that ‘informality’ should be understood as a category with shifting meaning, perception, and consequences that depend on which societal group is appropriating it. Therefore, ‘informality’ should be studied as a power relation that requires examining the context’s social construct, a range of actors, and their behavior. 14 Within this framework, it is even more critical to carefully examine the choice of using the term ‘informality’ in a settler-colonial context.

This paper argues that the use of ‘informality’ as a term to refer to Palestinian localities in Israel is particularly problematic due to the settler-colonial nature of the context. Therefore, it discusses some of the different factors that affect these localities and push them to ‘informal’ practices while situating them in a theoretical framework of settler-colonialism. To understand this issue, the paper engages with Wolfe’s definition of settler-colonialism and its ‘logic of elimination.’ 15

Theoretical Framework

Literature about settler-colonialism, namely the contributions of Patrick Wolfe and Lorenzo Veracini, stress the difference between settler-colonialism and classical colonialism by pointing out characteristics and structures of the former that imply a distinct formation understood as ‘structure not an event.’ 16 Settler-colonialism is a structure (and not an event) due to the fact that settler colonizers ‘come to stay,’ therefore, settler-colonialism’s temporality is continuous, whereby the past and present are closely connected. 17

Wolfe stresses that “Territoriality is settler-colonialism’s specific, irreducible element,” as territory is absolutely essential for a settler society to establish its new polity over. It is only by the total rejection of the indigenous presence, that settler-coloniality can sustain itself. Therefore, it is necessary to erase evidence of historic or ongoing sovereignty of the indigenous people. Wolfe refers to this conduct as the ‘logic of elimination’ explaining that it is the main driver of the settler-colonial ‘structure’ of conquest. In its ‘negative dimension’, the term refers to a colonial endeavor to the dissolution of native societies’ control over land. The ‘negative’ aspect of ‘elimination’ could vary in its forms and shapes; its strategies could range from ‘replacement,’ ‘assimilation,’ religious conversion, fragmentation of the native collective, to frontier homicide and genocide. Each colonial power favors different strategies depending on the locality’s historical circumstances. Whereas, the ‘positive dimension’ of ‘elimination’ is geared towards founding of a new exclusive colonial polity on the seized land. 18

The main motivation for the native’s ‘elimination’ lies in ‘access to territory.’ 19 Wolfe states that in order to achieve access to territory, the symbolic and physical ‘elimination’ of the natives’ bodies is necessary, creating a state of spatial and social cohesion. He calls this process the ‘creative destruction,’ that destroys to replace. 20 Furthermore, settler-colonial regimes introduce divisions in their relationship with the ‘other’ native population, producing and reproducing the unequal relationship in social structures that manifest settlers’ superiority in terms of race, religion, civilization or other socially constructed signifiers. 21 These dynamics translate spatially as the “dominant group appropriates the city apparatus to buttress its domination and expansion,” a process referred to as ‘urban ethnocracy’ by Yiftachel and Yacobi. This planned ethnicization results in the manipulation the local ethnic geography to advance the interests of a dominant ethnic group. 22

On the ‘urban informality’ front, Roy examines how the state formalizes or criminalizes different localities and different spatial configurations. The premise is that the modern state uses technologies of visibility such as counting, mapping and enumerating to govern its regime and subjects. 23 Contrary to this general premise, Roy argues states and authorities also use ‘unmapping’ 24 of cities as a practice. 25 This means that the state does not only determine what is ‘formal’ or ‘informal,’ but also actively uses ‘informalization’ as a tool of authority. The state declares localities as ‘informal’ to achieve ambiguity that allows new zonings, drawing new boundaries and reassigning land uses. 26 Moreover, Veracini relates these practices to settler-colonial powers stating that it is one of the methods they use to establish their political order as the only viable order. 27

It could be argued that assigning natives’ localities as ‘informal’ in settler-colonial contexts is a tool exploited by the settler-colonial power to legitimize and further implement its ‘eliminatory’ practices. Through condemning native localities to ‘informality’ and the process of ‘informalization,’ the settler-colonial power tries to disrupt the natives’ connection to their land by alleging that their urban practices or even their mere existence on a land is unofficial, illegitimate or even criminal. Equivalently, Veracini’s claims that one of the tactics that settler-colonial powers use in order to secure the erasure of the native, is to refute that indigenous peoples hold an attachment to the place. Consequently, the settler forcefully portrays the native as nomadic, rootless, unsettled, and with no sense of place. 28 Just as the violent transformation of the native to nomad is “naturalized as an unfortunate by-product of progress,” 29 so is the denouncement of ‘informality,’ which is portrayed as a ‘threat’ to progress that does not adhere to the rules of a modern society. This argument begins unfolding the complexity of using ‘informality’ in a settler-colonial context.

Settler-colonial Reading of Palestinian Localities

As a settler-colonial power, Israel operates in line with the ‘logic of elimination,’ which is mainly driven by acquiring ‘access to territory’ and requires ‘elimination’ of natives. It destroys to replace. 30 Theodor Herzl, founding father of the Zionist organization said “If I wish to substitute a new building for an old one, I must demolish before I construct.” 31 Israel operates according to this logic until today.

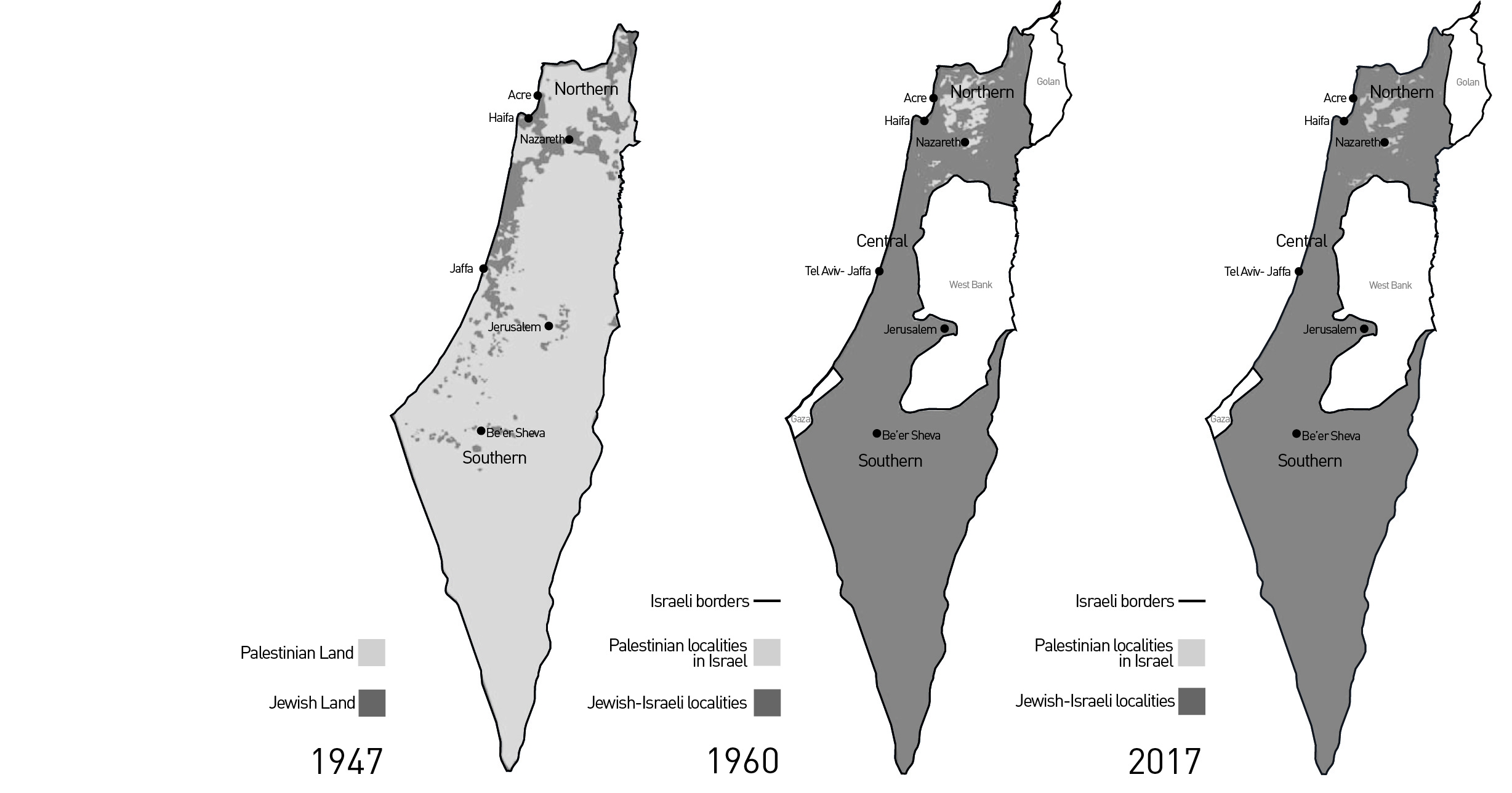

The ‘eliminatory’ practices intensified with the displacement of 750,000 Palestinians and the destruction of more than 500 Palestinian localities during the events of the 1948 war, 32 which Palestinians refer to as the Nakba. 33 As a result, the settler-colonial movement established Israel as its own independent state and confiscated around 92,6% of the private lands owned by Palestinian natives. 34 Right after the state’s establishment, Israel used martial law to control most of the remaining Palestinian localities within its borders in order to control Palestinians’ movements and maintain its control over the land, while it set up legal systems that insure it. 35 These legal systems embodied the ‘eliminatory’ logic of a settler-colonial state. That included establishing two primary laws which institutionalized massive land confiscation, ‘The Land Acquisition Law’ (1953) and ‘The Absentees’ Property Law’ (1950). The former expropriated 1.2- 1.3 million dunams 36 of land from the Palestinian population for “essential settlement and development needs,” while the latter transferred all the property possessed or used by Palestinians who became refugees to the state of Israel. Legalizing land confiscation has continued until recently, when an Amendment to ‘The Land Ordinance Law’ (Acquisition for Public Purposes) was enacted in 2010 mainly to confirm state ownership of land confiscated from Palestinians in perpetuity. 37

38 For Israel to strengthen Jewish-Israeli presence throughout its newly occupied territory, it operated towards the ‘positive’ dimension of ‘elimination.’ This meant replacing the Palestinian natives with ethnically exclusive Israeli-Jewish immigrants. 39 Here, district and national zoning and planning institutions and policies have been (and still are) crucial for Israel to “seize, retain, expropriate, reallocate and reclassify Palestinian lands,” in order to expand its Jewish-Israeli settlements. 40 These processes of ‘elimination,’ while constantly hindering the expansion of the native Palestinians’ space and simultaneously expanding Israeli Jewish-settlements over parts of their lands and surrounding their villages and towns, have culminated in the fragmentation of the Palestinains’ space and the encla vization of its inhabitants. Such enclavization of the Palestinian citizens of Israel can be observed in two main ways: first, Palestinian towns are enclaves within national parks and reserves, forests, Jewish settlements, roads and infrastructure, 41 and second, Palestinian neighborhoods are enclaves within ‘mixed’ Israeli cities. Yiftachel and Yacobi argue that studying the plans of Israel’s ‘mixed cities’ (e.g. Lod, Acre) teaches an array of its objectives such as ‘keeping the Jewish character’ and “combating the ‘danger’ of increasing Arab population which might create a ‘demographic threat’ to the city.” In these cities, dense Jewish neighborhoods were rapidly developed around what previously were Palestinian localities, creating these enclaves manifesting Israel’s ‘urban ethnocracy.’ 42 Due to the political, social and economic conditions of settler-colonialism, Palestinian towns started to spatially change. 43 Israeli state planners focused on creating new modern Jewish settlements at the expense of the Palestinian minority, 44 and drawing up national master plans that discriminate against the Palestinian citizens by excluding them from the planning process and ignoring their needs. 45 Badil’s 46 report states that these localities face obstacles on all bureaucratic levels, which is reflected in lack of planning, postponing or rejecting most local development plans, and preventing the implementation of the sparse number of plans that are rarely actually approved. These factors are but a few of various indicators of systematic discrimination that these localities face. Consequently, many Palestinian localities in Israel had to transform from rural to urban localities without an overarching strategy. 47

The ‘informalization’ of Palestinian localities in Israel

Combining all of the settler-colonial practices that persisted throughout the years along with the fact that the Palestinian minority grew 10-12 times larger since 1948, 48 and the fact that Israel did not establish a single Palestinian village, town or city since 1948 (in contrast to more than 700 new Jewish Israeli towns) 49 , resulted in severe living conditions that Palestinian localities face today. High density, overcrowding, lack of infrastructure and severe housing shortage became major issues for Palestinian localities in Israel. 50

Hence, the inhabitants of Palestinian localities were left with very limited options if they wish to stay in their hometowns. Therefore, usually when the family expands, additions are made to existing buildings or plots that are already developed. These additions are often classified as ‘illegal’ since they break certain building regulations set by the state, like ‘building coverage ratio,’ ‘floor-area ratio’ and others. Meanwhile, receiving permits to build on other plots is often nearly impossible for the lack of master plans for these localities. 51 Buildings without permits are indeed one dominant feature of the long term discriminatory planning policies of Israel towards the Palestinian localities.

Furthermore, Yiftachel and Yacobi draw attention to the implications of the settler society structure on Palestinian localities in Israel’s ‘mixed cities.’ They state that ‘mixed cities’ such as Haifa, Jaffa, Acre etc. turn into ‘urban ethnocracies’ where Palestinian presence is constantly delegitimized and portrayed as ‘dangerous.’ The physical translation of this logic results in neighbourhoods ‘invisible’ by the urban authorities or recognized neighbourhoods with lower levels of planning, far too little services and exclusion from the city’s communal life and policymaking. 52 This dynamic generates discriminatory policies and reinforces the discursive construction of Palestinians as ‘dangerous,’ which are in turn also responsible for the emergence of ‘informality’ and ‘various degrees of ‘illegality.’

On these grounds, one can conclude that the relegation of Palestinian urbanism to the sphere of the 'informal' is an extension of Israeli settler colonial logics. These policies do not only disregard the urban culture and daily needs of indigenous Palestinian communities, but constantly seek to dismember the Palestinian space and minimize it.

The problematics of ‘informality’

Going back to Roy’s observations in order to further highlight the problematics of using this terminology in regard to Palestinian urbanism in Israel, she reminds us that various forms of ‘informality’ exist outside the marginalized and weaker communities. However, they are rarely referred to as ‘informal’ or evaluated as such, even though they do not conform to master plans and are not in any way more legal than the ‘informalities’ in the other localities. This is merely due to the fact that they occur in urban geographies with a different social class, race or ethnicity. These kinds of spatial expressions get to be developed, maintained, capitalized and when desired, easily converted into a formal spatiality. 53 Similar line of thinking can be seen in Yiftachel’s analysis of ‘informal’ urbanism in the Palestinian-Israeli context:

The understanding of gray space as stretching over the entire spectrum, from powerful developers to landless and homeless ‘invaders,’ helps us conceptualize two associated dynamics we may term here ‘whitening’ and ‘blackening.’ The former alludes to the tendency of the system to ‘launder’ gray spaces created ‘from above’ by powerful or favorable interests. The latter denotes the process of ‘solving’ the problem of marginalized gray space by destruction, expulsion or elimination. The state's violent power is put into action, turning gray into black. 54

‘Blackening’ Palestinian ‘informalities’

Ascribing ‘informality’ to Palestinian locality designates it as ‘illegal,’ ‘criminal,’ ‘dangerous,’ and ‘illegitimate,’ and is consequently conjoined with punitive measures. These discriminatory conditions and the punitive practices that they generate are tightly connected to Israel’s ‘eliminatory’ logics whereby the native Palestinians’ constitute a hindrance to the expansion of its frontier. 55 As such, ‘informalization’ constitutes one of the dominant Israeli strategies through which Israel operates its ‘eliminatory’ policies against Palestinian localities, subjecting them to various forms of violence, e.g. fines, evictions, demolition orders, actual demolitions, impossibility to have a house etc.

This section demonstrates a couple of illustrations from recent years that depict such ‘informalization’ processes and the violence that they produce, namely the Jerusalem 2000 Plan, the Prawer Plan and the Kaminitz Law.

The Jerusalem 2000 Plan is a master plan that outlines guidelines and strategies for various fields, such as housing, archaeology, tourism, education, economy and transport. 56 Jabareen’s analysis of the plan is that it’s “outwardly hostile toward the Palestinian inhabitants of the city, characterizing their existing spaces as ‘illegal,’ ‘chaotic,’ and ‘extremely problematic,’ and charging the Palestinian population with ‘evading planning law’ and causing ‘urban planning chaos’.” 57 Furthermore, he emphasizes that according to this perception, Jerusalem 2000 calls for penalizing the Palestinians with more severe punitive measures in order to limit ‘illegal’ housing and urban planning among Palestinians. 58

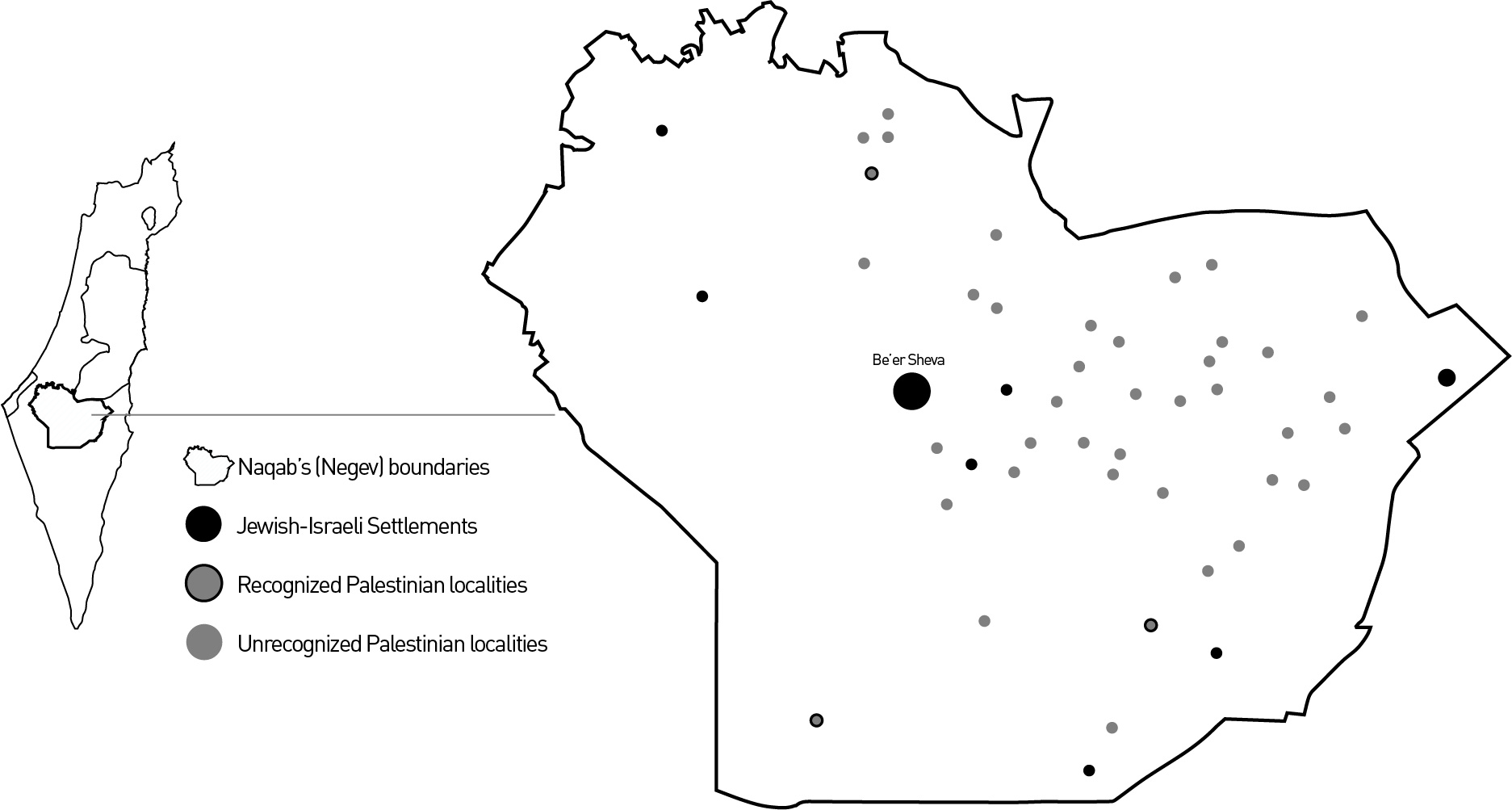

The second case deals with the unrecognized Palestinian Bedouin villages of the Naqab area (Negev). Despite the community’s long history in the area, 36 of its villages (home to 70,000 Palestinians), are not recognized by the Israeli state. Thereby, Israel never gave them any representations on its formal maps, 59 60 rendering them ‘illegal’ in their entireties. 61 This ‘informalization’ act of ‘unmapping,’ turned these communities invisible and subjected them to variable types of daily violence, since its implications range from daily life adversity, lack of infrastructure and services, to constant threats and actualization of demolitions.

Israel bases the approach towards these localities on the false premise that the Bedouins have no legal claim to their ancestral land in the Naqab (Negev) and therefore considers them as trespassers on state land. This premise paved the way to drafting the governmental Prawer Plan, which was approved by the Israeli government in 2011, and if fully implemented, would lead to the destruction of all 36 villages resulting in the forced displacement of their inhabitants. 62 63 However, the plan was put on hold in 2013 due to mass protests against it by the Palestinian Bedouin community together with the rest of the country’s Palestinian community. 64 65

The last case demonstrates ‘informalization’ through Amendment 166 to Israel’s Construction Law, mainly referred to as the Kaminitz Law, which was introduced in 2016 and finally put into motion in December 2018. This law demands stronger enforcements of the planning and construction laws. It is based on the ‘Kaminitz Report’ by a team dealing with a phenomenon of illegal construction. 66 After examining the law, civil right organizations and planning rights associations 67 drafted a position paper, in which they stated that the purpose of it is mainly to expand the punitive powers of administrative entities, especially national planning entities and planning enforcement entities. These entities are able to impose more planning regulations and can increase the amounts of fines and prison terms if the regulations are violated. 68 The position paper emphasizes the importance of the new law’s implications on the Arab citizen, especially in the context it was submitted, referring to Government Resolution No. 1559 that specifically targets the phenomenon of illegal building in Palestinian localities in Israel. 69 70 Given that most Palestinian localities do not have state-sanctioned master plans, 71 issuing building permits became impossible, and hence the Kaminitz Law came to provide a sole punitive ‘solution’ to ‘illegal’ construction in Palestinian localities.

Within only nine months, the law managed to penalize Palestinian citizens in the amount of 12 million Shekels (3,42 million US Dollars) and carry out 154 orders of demolition or to halt construction. Fines issued by this law are five times the former court fines. 72 Additionally, the law allows for these orders and fines to be issued administratively by ordinary inspectors without the need to go through legal mechanisms. 73

‘Whitening’ Jewish-Israeli ‘informalities’

The recent events that transpired in enforcing Kaminitz Law revealed illegal constructions among certain Jewish settlements, such as the Moshavim, 74 as they have received fines and punishments as well. The affected Moshavim residents were outraged having discovered that the law also applies to them and claimed that they were “disproportionately targeted by enforcement.” 75 In response, Ayelet Shaked, Minister of Justice and one of the ministers to advance this law, said the law’s “goal was to deal with building violations among the non-Jewish population, where it is common […] Unfortunately it is being used disproportionately against elderly farmers being issued heavy fines”. In a taped interview she used the phrasing “we intended to bless, instead we cursed” meaning that accidentally the law backfired to target Jewish populations instead of focusing solely on Palestinian communities. 76 Shaked goes on further to reassure the Moshavim residents promising them “to do whatever it takes to change the regulation.” 77 As such, Shaked lies bear the intention behind the Kaminitz Law, so to target exclusively the non-Jewish localities, i.e. those of the Palestinians which are ‘known’ for their ‘informality’ and ‘illegality.’ Immense enforcement measures on illegal construction in Jewish-Israeli localities have been generally avoided by the authorities until the Kaminitz Law was passed. Shay Hajaj, chairman of the Israel Regional Councils Association, confirms this stating that before passing Kaminitz Law, the state followed a non-enforcement policy in the Moshavim. He asks the authorities to “have some patience” as part of the structures “still have the chance to be legally recognized.” Additionally, he stated that in a debate in the secretariat of his Likud party, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had promised to freeze enforcement efforts in the Moshavim for three years. 78

The authorities’ decades-long active avoidance of ‘informalities’ in Jewish settlements and the forthright declarations by Shaked and Netanyahu accentuate two major issues. First, the terminology of ‘informality’ and ‘illegality’ in the settler-colonial context of Israel, is associated solely with the indigenous Palestinian community, the marginalized ethnic group, even though similar practices commonly exist among the Jewish settler society as well. Second, however, they admit that ‘informality’ among the dominant Jewish ethnic group was and will continue to be ‘whitened,’ as they are treated in a forgiving and tolerant manner. Meaning, they admit to taking on selective enforcement as a practice as well.

Conclusion

As a settler-colonial regime, Israel has been operating to ‘eliminate’ the native Palestinian for decades, a process which is directed towards minimizing the Palestinian natives’ hold over territory conjoined with the expansion of Jewish-only spaces to maintain its ‘ethnocractic’ endeavor. This logic led to massive land confiscations and the establishment of planning policies that discriminate against the indigenous Palestinian community and hinder its development. Therefore, the initial reason Palestinian localities are consistently relegated to ‘informal’ urban practices is the by-product of Israel’s spatial agenda that is impelled by the logic of ‘elimination.’

Moreover, the exclusive classification of the Palestinian localities as ‘informal’ is informed by Israel’s settler-colonial logics and practices that aim at maintaining its ‘ethnocracy.’ As this terminology sustains the negative perception of these localities and their communities, whether by the public, scholars or official state authorities, this in turn preserves the ethnic divide and deepens the gaps between the different ethnic groups. This has been illustrated through ways in which Israeli authorities and the political echelon treat ‘informalities’ among the dominant Jewish ethnic group, which are usually ignored and not classified as such. However, when they are unintentionally identified as such, as demonstrated with the Kaminitz Law, they are approached with ‘whitening’ strategies such as toleration and legitimization.

On the other hand, the relationship between Israel and its Palestinian citizens in the realm of urban construction has been almost exclusively run by punitive measures. By designating the terminology of ‘informality’ to Palestinian localities, Israel attempts to legitimize its ‘blackening’ approach towards them and to justify the punitive measures it enforces against them (e.g. fines, evacuations, demolitions), which have proven to get more severe with time. Therefore, this paper argues that using the terminology of ‘informality’ to refer to Palestinian localities further accredits and reinforces the settler-colonial objectives of Israel’s planning, legal, political and social systems, that intend to suppress, control and restrict the Palestinian community and its development.

Breaking out of this cycle and the deadlock of ‘informality’ requires taking heed to the natives’ spatial expressions, learn their needs, how they visualize their urban environments, and pay attention to the embodied knowledge in their localities and read them as environments with their own values and logic. However, in order to do that successfully, it is first necessary to take on decolonialization practices, form decolonializing initiatives and understandings of the natives’ society, and their spatial and urban practices. This includes breaking down political ‘eliminatory’ systems and settler-colonial social structures, disposing settler-colonial readings of indigenous localities, rethinking the settler-colonial narratives, and finally establishing new inclusive participatory practices and counter action.

Author

Venus Ayoub is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, currently pursuing a Master’s Degree in Urban Design at the Technical University of Berlin. She holds a B.Arch from the Technion, Haifa (2014). She is interested in urban planning, particularly in the Palestinian-Israeli context.

-

Habitat Universities Thematic Hub, “Informal Urbanism,” accessed September 30,2019,

https://unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Hub-Informal-Urbanism.pdf ↩ -

Ananya Roy, “Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning,” Journal of the American Planning Association, no. 71 (2005): 147.

↩ -

Differing from some of the literature that this article examines, I use the term ‘Palestinian towns/ localities’ instead of ‘Arab towns’, believing that it is the more accurate terminology as it refers closer to the unique experience of the Palestinian minority. ↩

-

Yosef Jabareen, “The Right to Space Production and the Right to Necessity: Insurgent versus Legal Rights of Palestinians in Jerusalem,” Planning Theory 16, no. 1 (February 2017): 6–31, https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095215591675. ↩

-

‘Negev’ in Hebrew, a region in southern Israel with Be’er Sheva as its main city. ↩

-

Yosef Jabareen and Orwa Switat, “Insurgent Informality: The Struggle over Space Production between the Israeli State and Its Palestinian Bedouin Communities,” Space and Polity 23, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 92–113, https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2019.1587258. ↩

-

Faranak Miraftab, “Insurgent Planning: Situating Radical Planning in the Global South,” in Readings in Planning Theory, ed. Susan S. Fainstein and James DeFilippis (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2015), 480–98, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119084679.ch24. ↩

-

Jabareen and Switat, “Insurgent Informality.” ↩

-

UN-Habitat, Urbanization and Development: Emerging Futures, world cities report (Nairobi: UN-Habitat,2016), https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/WCR-2016-WEB.pdf. ↩

-

Oren Yiftachel, “Theoretical Notes On ‘Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?,” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (February 2009): 88–100, 87, https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095208099300; Oren Yiftachel, “Critical Theory and ‘Gray Space’: Mobilization of the Colonized,” City 13, no. 2–3 (June 2009): 246–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902982227. ↩

-

Noah J. Durst and Jake Wegmann, “Informal Housing in the United States: Informal Housing In The United States,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41, no. 2 (March 2017): 282–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12444. ↩

-

Durst and Wegmann. ↩

-

Durst and Wegmann. ↩

-

Frank I Müller, “Urban Informality as a Signifier: Performing Urban Reordering in Suburban Rio de Janeiro,” International Sociology, vol. 32(4) (2017): 493- 511. ↩

-

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native,” Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240. ↩

-

Patrick Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native”, Journal of Genocide Research 8, no. 4 (2006): 387–409, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240; Lorenzo Veracini, “‘Settler-colonialism’: Career of a Concept,” Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 41, no. 2 (2013): 313–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/03086534.2013.768099. ↩

-

Omar Jabary-Salamanca et al., “Past Is Present: Settler-colonialism in Palestine,” Settler-colonial Studies 2, no. 1 (2012): 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2012.10648823. ↩

-

Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” ↩

-

Wolfe. ↩

-

Patrick Wolfe, “Palestine, Project Europe and the (Un-)Making of the New Jew: In Memory of Edward Said,” in Edward Said: The Legacy of a Public Intellectual (Melbourne University Press, 2007), 313–37. ↩

-

Wolfe. ↩

-

Oren Yiftachel and Haim Yacobi, “Urban Ethnocracy: Ethnicization and the Production of Space in an Israeli ‘Mixed City,’” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21, no. 6 (December 2003): 673–93, https://doi.org/10.1068/d47j. ↩

-

Roy, “Urban Informality.” ↩

-

The deliberate lack of representation in cartographies. ↩

-

Ananya Roy, City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty, Globalization and Community, v. 10 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). ↩

-

Roy, “Urban Informality.” ↩

-

Lorenzo Veracini, “On Settlerness,” Borderlands , no.1 (November 2011): 1-17. ↩

-

Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” ↩

-

Wolfe. ↩

-

Wolfe. ↩

-

Theodor Herzl, Old–New Land [Altneuland, 1902], Lotta Levensohn, trans. (New York: M. Wiener 1941): 38. ↩

-

Badil, “Discriminatory Zoning and Planning,” Forced Population Transfer:The Case of Palestine, no. 17 (December 2014), 5-57. ↩

-

Arabic term literally meaning “the catastrophe”. It refers to the first round of massive population transfer undertaken by the Zionist movement and Israel in the period between November 1947 and the cease- fire agreements with Arab states in 1949. (see Badil, 2017) ↩

-

Honaida Ghanim, “The Nakba”, in The Palestinians in Israel- Readings in History, Politics and Society (Haifa: Mada al- Carmel, 2011), 17. ↩

-

Adam Raz, “Secret Israeli Document Reveals Plan to Keep Arabs Off Their Lands,” Haaretz, January 31, 2020, https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-secret-israeli-document-reveals-plan-to-keep-arabs-off-their-lands-1.8473226. ↩

-

A measure of land area, equals to approximately 900 square meters. ↩

-

Katie Hesketh and Adalah (Organization), The Inequality Report: The Palestinian Arab Minority in Israel, 2011. ↩

-

Visualizing Palestine. “Palestinian Land Day - An Explainer.” Accessed February 5, 2020.https://www.guengl.eu/issues/explainers/palestinian-land-day-an-explainer/. ↩

-

Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” ↩

-

This can be observed in the ‘Sharon Plan’ (1948-1953), which considered the land as mainly ‘empty’ and focused on ‘replacement’- an accelerated Jewish colonization process. (see Jabareen and Switat “Insurgent Informality”) ↩

-

Badil, “Discriminatory Zoning and Planning.” ↩

-

Oren Yiftachel and Haim Yacobi, “Urban Ethnocracy: Ethnicization and the Production of Space in an Israeli ‘Mixed City’,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21, no. 6 (December 2003): 680, https://doi.org/10.1068/d47j. ↩

-

Maisa Totry-Fakhoury and Nurit Alfasi, “From Abstract Principles to Specific Urban Order: Applying Complexity Theory for Analyzing Arab-Palestinian Towns in Israel,” Cities 62 (February 2017): 28–40, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.12.001. ↩

-

Totry-Fakhoury and Alfasi. ↩

-

Badil, “Discriminatory Zoning and Planning.”

↩ -

Badil is a resource center for Palestinian residency and refugee rights. It was established in 1998 as an independent and nonprofit organization that is committed to protect and promote the rights of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced. ↩

-

Badil, “Discriminatory Zoning and Planning.” ↩

-

Nurit Alfasi, “Doomed to Informality: Familial versus Modern Planning in Arab Towns in Israel,” Planning Theory & Practice 15, no. 2 (April 3, 2014): 170–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.903291. ↩

-

Oren Yiftachel, “Palestinian Citizenship in Israel,” in The Palestinians in Israel- Readings in History, Politics and Society (Haifa:Mada al-Carmel, 2011), 133. ↩

-

Nurit Alfasi, “Doomed to Informality: Familial versus Modern Planning in Arab Towns in Israel,” Planning Theory & Practice 15, no. 2 (April 3, 2014): 170–86, https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.903291. ↩

-

Alfasi, “Doomed to Informality.” ↩

-

Yiftachel and Yacobi, “Urban Ethnocracy.” ↩

-

Roy, “Urban Informality.” ↩

-

Yiftachel, “Theoretical Notes On `Gray Cities’," 91.

-

Wolfe, “Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” ↩

-

Francesco Chiodelli, “The Jerusalem Master Plan: Planning into the Conflict,” Jerusalem Quarterly 51, (January 2012): 5-20. ↩

-

Jabareen, “The Right to Space Production and the Right to Necessity,”11. ↩

-

Jabareen. ↩

-

Jabareen and Switat, “Insurgent Informality.” ↩

-

Yiftachel and Yacobi, “Urban Ethnocracy.” ↩

-

Yiftachel, “Theoretical Notes On `Gray Cities’.” ↩

-

Adalah (organization), “The dangerous implications of the Israeli Supreme Court’s decision to allow the forced displacement of Atir-Umm al-Hiran for the remaining unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Naqab (Negev),” (2016): 1-5. https://www.adalah.org/uploads/Dangerous-Implications-SCT-Atir-Umm-al-Hiran-updated-Feb-2016.pdf. ↩

-

Badil, “Discriminatory Zoning and Planning,” Forced Population Transfer:The Case of Palestine, no. 17 (December 2014):5-57.

↩ -

Jabareen and Switat, “Insurgent Informality.” ↩

-

However, Israel proceeded through another means attempting to achieve Prawer Plan’s goals. A planning campaign developed by The Negev Development Authority, which aims to displace the Bedouin community in order to start ‘developing’ new residential areas (See Jabareen and Switat, 2019). ↩

-

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning, Massawa Center, Sikkuy, Mizan Center and Bimkom, “Kaminitz Law: Position Paper,” last modified January 29,2017, https://law.acri.org.il//en/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017.2.5-keminitz-law-position-paper-eng.pdf ↩

-

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning, Bimkomm, Mosawa Center, Mizan for Human Rights and The Association for the advancement of Civic Equality ↩

-

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning, Massawa Center, Sikkuy, Mizan Center and Bimkom, “Keminitz Law: Position Paper,” last modified January 29,2017, https://law.acri.org.il//en/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017.2.5-keminitz-law-position-paper-eng.pdf.s ↩

-

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning, Massawa Center, Sikkuy, Mizan Center and Bimkom, “Keminitz Law: Position Paper,” last modified January 29,2017, https://law.acri.org.il//en/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017.2.5-keminitz-law-position-paper-eng.pdf.s ↩

-

The government services and information website , “Government Resolution No. 1559,” accessed October 12, 2019, https://www.gov.il/he/Departments/policies/2016_des1559. ↩

-

Dotan Levy, “Israeli Farmers Claim New Regulation Meant to Target Arabs Is Being Used Against Them,” CTECH - www.calcalistech.com, October 16, 2019, https://www.calcalistech.com/ctech/articles/0,7340,L-3771969,00.html. ↩

-

Arab48, “Lawyer Qais Naser: This is what we received from Kaminitz Law,” September 21, 2019, https://www.arab48.com/??????/??????/2019/09/21/???????-???-????-??? . ↩

-

The Association for Civil Rights in Israel, The Arab Center for Alternative Planning, Massawa Center, Sikkuy, Mizan Center and Bimkom, “Keminitz Law: Position Paper,” last modified January 29,2017, https://law.acri.org.il//en/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2017.2.5-keminitz-law-position-paper-eng.pdf.s ↩

-

A type of Israeli Jewish towns known for their cooperative agricultural community. ↩

-

Levy, “Israeli Farmers Claim New Regulation Meant to Target Arabs Is Being Used Against Them.” ↩

-

Tamar Kaplanski, “This Law was intended only for Arabs,” last modified September 11,2019, https://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-5586515,00.html. ↩

-

Levy, “Israeli Farmers Claim New Regulation Meant to Target Arabs Is Being Used Against Them.” ↩

-

Levy.