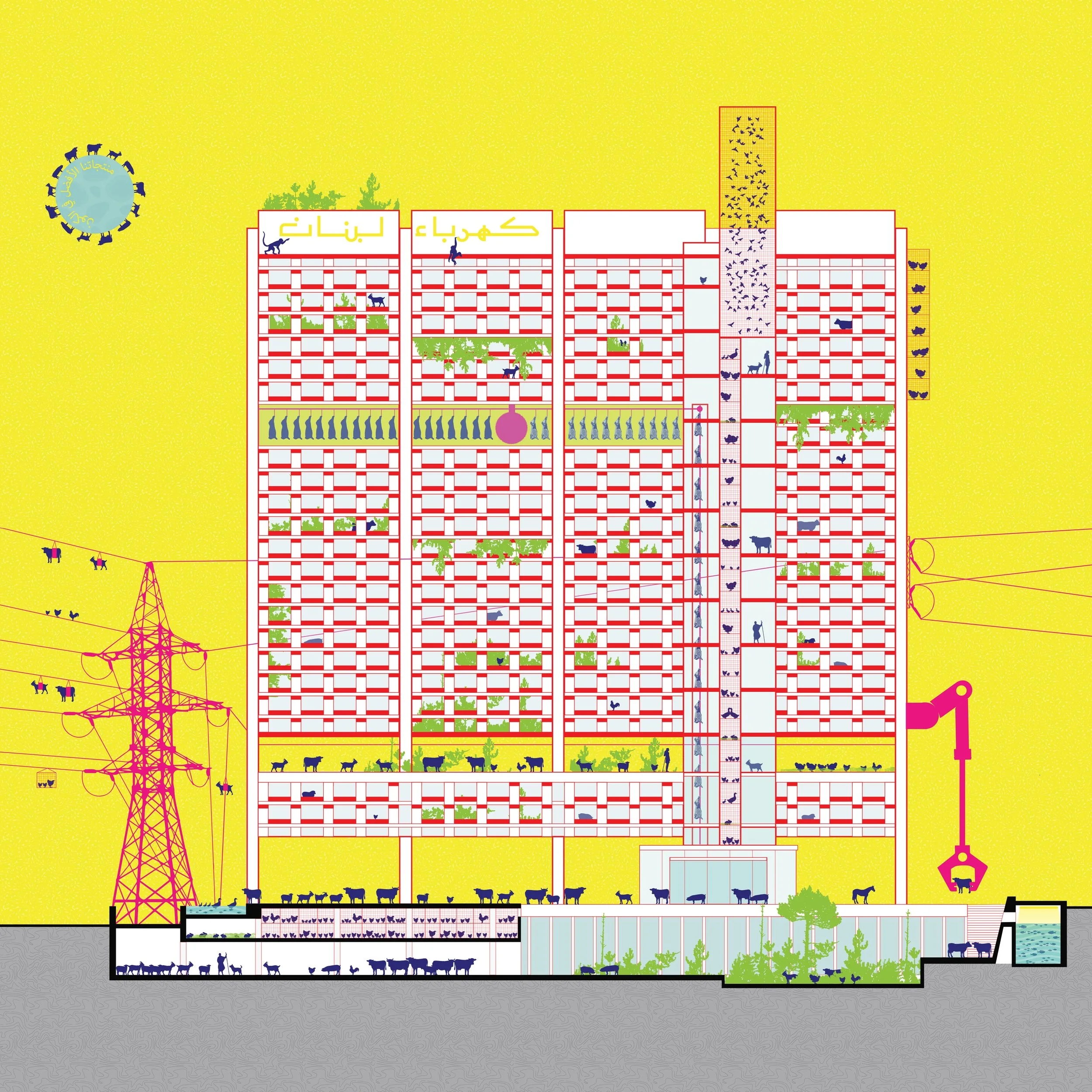

Electricité du Liban: A Vertical Mazra'a

Figure 1. EDL Vertical Mazraa' is a cynical illustration that re-imagines the state-owned EDL (Electricity of Lebanon) Headquarters as an Urban Vertical farm controlled by competing entities.

In August 2018, the Lebanese woke up to several media outbreaks reporting the existence of a makeshift chicken coop at the state-owned electricity headquarters - Electricité du Liban (EDL). The coop, made of wooden cages and electric incubators, hosted an array of avian species such as chicken and quail. The claims made by the media were later confirmed by EDL's spokesperson and the Ministry of Energy and Water. The chicken coop generated another fleeting public outcry on the streets of Beirut[1]. What caused outrage was the fact that the coop was supplied with 24/7 electricity when the city of Beirut was being subjected that summer to blackouts of more than 10 hours a day. This controversy and the modern ruins that the EDL represent speak to the failures of the colonial and postcolonial project of modernisation in the Levant.

Power cuts have long been a part of life in Lebanon. The dysfunctional electricity sector is a product of the legacies of the French colonial project, government corruption, and foreign intervention. After Lebanon’s independence in 1943, Beirut seemed to be a prospering metropolis, at least to the wealthy and bourgeoisie in the city. The 1950s and 1960s were times where the newly independent nation-state focused on situating itself as a major regional player. Embracing the promise of modern infrastructures, the elite political class hoped to build a modern country based on the blueprint left by the French colonial empire. This period witnessed a surge in architectural development embedded in modernist ideology introduced by young Lebanese architects that had recently graduated from European universities, mainly from France. The government especially under Fouad Chehab presidency mobilized these young architects to establish a new national identity, a “modernist” ethos, that had its roots in Europe, and which sought to counter Arab nationalism in the country and efforts to establish modern sovereign states in the region.[2] At that time, France was – and unfortunately still is – considered as the ‘mother country’ by most of the ruling political figures.

The period's modernist optimism is exemplified by EDL headquarters, designed by the architect Pierre Neema and CETA group in 1965. Pierre Neema was one of the prominent French trained modernist architects in Lebanon. After studying in France, and several years of training in various Parisian architecture firms, he decided to return to Lebanon in the 1960s and established the CETA group, a team of Lebanese and French architects and engineers including Jacques Aractingi, Joseph Nassar, and Jean-Noel Conan.[3] In addition to the EDL, Neema and CETA group designed and built emblematic buildings such as the Postal, Telegraph and Telephone (PTT) service building in Bir Hassan, the EDL power station in Furn El Chebbak, and the Maison de L'artisan Libanais.

The EDL was designed to be a modernist edifice. This massive concrete structure hovers above a sunken public courtyard, offering the neighbourhood a nestled urban pocket and a view towards the Mediterranean Sea, a space of generosity where massive institutional buildings seem to welcome the public and convey a sense of transparency. The company’s headquarters assert the ruling government’s aspiration to supply services far into the rural territories of Lebanon. It was intended to be an icon not only to Beiruties but for all citizens throughout the country – a modernist infrastructural building that represented the newly established state of Lebanon as a concrete materialization of a homeland for all its citizens. Today, the EDL’s worn façade, its collapsed service systems, archaic office spaces, and gated sunken courtyard, exemplify the disappointments and failure of modernity in Lebanon. Indeed, the building that was supposed to represent a modern utopian dream tells the story of the aspirations and the failures of the country.

In Lebanon, there is a colloquial word people use to describe governmental institutions: "Mazra’a." Mazra’a means farm in Arabic, however the Lebanese have adopted the term to vaguely express the chaotic state of governmental institutions. The EDL’s headquarters is perceived as a Mazra’a. But why Mazra’a? Some, mainly the urban bourgeoisie, link Mazra’a to the rural, a place that did not embrace modernity and civilization. Others use the word as an analogy for feudalism – a system of hierarchy, where lords have rights over virtually everything and look at their “subjects'' as mere objects stripped of all rights and agency. My great uncle, Mohana Al Safadi, refused to use the word Mazra’a. He always referred to our farm as “ʼArd,” which is the Arabic word for land or earth. He believed ʼArd to be a place of nurture, a generous and giving extension of the ecosystem. In a way, I believe he looked at ʼArd as a complex and diverse territory beyond private ownership, a place cared for by its custodians where foragers, herders, and non-human species can inhabit and move freely. ‘Ard, as in my great uncle’s understanding, recalls a healthy ecosystem with transspecies alliances and relationships that ensures regeneration.

Unlike ʼArd, a place of belonging, the modern Mazra’a departs from the traditional and historic farming practices in the region. The term in Lebanon is used as a synonym to the industrial farm, a foreign concept introduced by modernity with no regards to natural cycles, context, and relationships among living beings – human and non-human. It is a site of monocultures and mass production guided by strict economic structures, where beings are exploited and isolated from their natural habitat, a system that needs continuous intervention in order to maintain short term profit at the cost of longevity and overall health of the ecosystem. Lebanon, like a modern Mazra’a, was designed to be isolated and exploited by the colonial powers and, later, by political and economic elites. Separated from its natural and historic relationships with neighbouring communities, the country has been left with minimal resources, unable to exist without continuous foreign intervention. Just like a factory farm – simply Mazra’a as locals refer to it, the inhabitants of this land are exploited in every possible way to generate gains – economic, political, or otherwise – for few local and foreign players. A century after the inception of Lebanon the Mazra’a mentality has seeped into almost every aspect of Lebanese life, from public services to institutions, turning the country into the Republic of Mazra’a. Like other governmental institutions, the history of EDL is entangled with the history of Lebanon, both “projects” designed as a modern solution to the needs and aspirations of the people of this territory, each doomed to fail at the hand of the other.

Notes

[1] “عامل يربي الدواجن في مقر مؤسسة كهرباء لبنان,” Al Arabiya, accessed April 24, 2023.

[2] Eric Verdeil, Beyrouth et ses urbanistes: une ville en plans (1946-1975), (Beirut: Presses de l'Ifpo, 2010), 81-106. http://books.openedition.org/ifpo/2170.

[3] Georges Joseph Arbid, “PRACTICING MODERNISM IN BEIRUT ARCHITECTURE IN LEBANON, 1946-1970,” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2002), 49.

Bio

Iyad Abou Gaida is a Lebanese architect and researcher. Iyad worked for offices based in Tokyo, Beirut and New York. Iyad’s research engages ecologies of human and non-human beings to address aesthetic and socio-political urgencies for architecture and urbanism across dimensions and geographies. Iyad is a Co-founder of “EcoRove: Shifting territories and the displaced,” a collaborative project that studies living beings in the Critical Zone.

A Visual Essay by Marwa Shykhon