An ‘Arab’ urban scholarship? Navigating the Tensions of Regional Categories

Ibrahim Abdou

Introduction: Regionalism and New Territories of Urban Knowledge Production

Historically, global power structures have reflected hierarchal divides in urban theory, with western centres of political and economic privilege often serving as ‘legitimate’ producers of knowledge. Other cities were dismissed as less significant and independently less worthy of study. In response, particularly in the last two decades, scholars have called for decolonizing knowledge and realigning the canon of urban theory to include the experience of cities beyond those of western Europe and the United States. 1 Consequently, the complexity and insight of previously excluded regions has since been the subject of academic research and debate. However, much of this new urban research is being shaped by regionalism, which is the process of labelling, positioning and territorializing urban research as belonging to a certain region. For instance, a recent wave of initiatives from the Arab world aims for an urban scholarship that reveals the contextual specificity of Arab cities and speaks back to reductive, stigmatizing and fetichizing perceptions of the region. 2

This essay investigates this emerging regionalism within urban knowledge production, with a particular focus on the Arab region. Using the opportunity of the debut of yet another regional platform of urban research, Arab Urbanism, I explore why regionalism has been needed, where it has been useful, and why we need to question, rethink and even go beyond regional categories. The first part of the essay focuses on questioning the very regional category of ‘Arab’ where I discuss its origin, benefit and inherent tensions, while the second part analyses the actual work of specific Arab urban initiatives summarizing what they stand for.

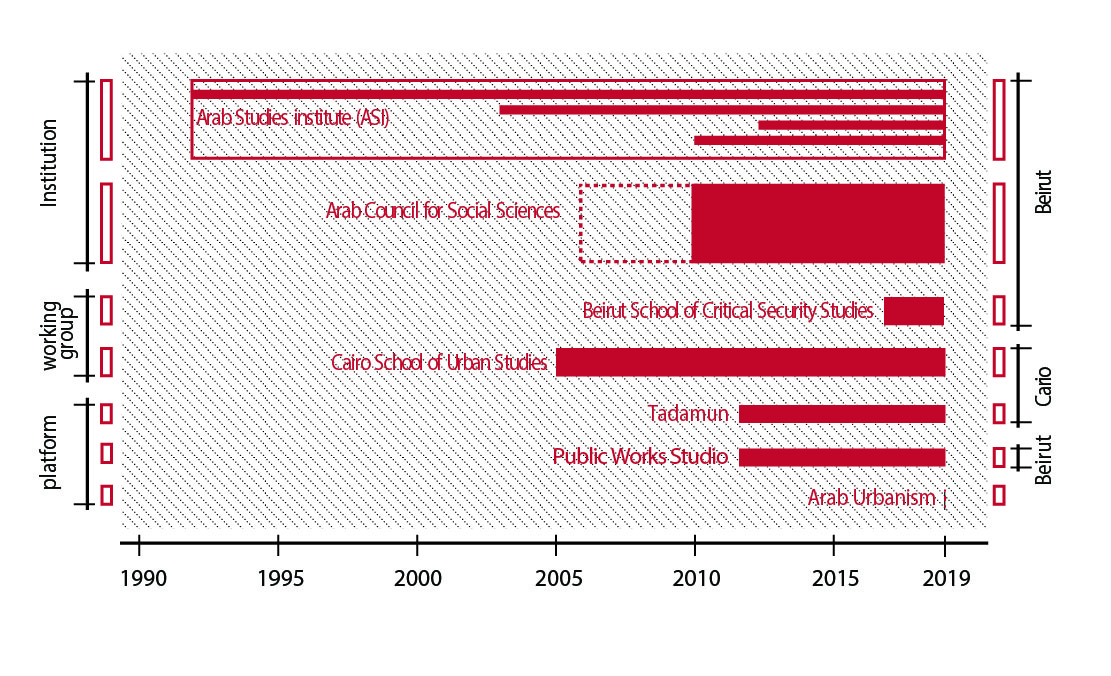

In order to empirically address these questions, I use the work of seven recently founded Arab initiatives (including councils, institutes, working groups and platforms) 3 to serve as a useful lens of analysis (figure 2). 4 Primarily based in Beirut and Cairo, these initiatives span several organizational levels and their scope and nature of work vary. At the regional scale, the Arab Council for Social Science (ACSS) is an institution that aims at strengthening social science research and supporting knowledge production in sustainable ways. Similarly, the Arab Studies Institute (ASI), based in Washington D.C. but with a local Beirut branch, is an umbrella organization with five subdivisions that produce different forms of knowledge including the widely read online magazine Jadaliyya. At an intermediary scale, I include two working groups, each encompassing a body of multi-disciplinary scholars who share a similar commitment to critical research in the region: the Beirut School of Critical Security Studies and the Cairo School of Urban Studies. While the Beirut School is consolidated as a sustainable working group under ACSS, the Cairo School was only a temporary collaboration that aimed to produce a specific output. Finally, at the micro-scale, three research-oriented initiatives generate accessible written analysis and visualizations which focus on the city, governance structures and local policies. These include: Tadamun, a dedicated research platform in Cairo that was jointly initiated by Takween, a community development association, and the American University in Washington D.C.; Beirut Urban Lab, a multidisciplinary research space based at the American University in Beirut; and Public Works Studio, a creative and multidisciplinary studio in Beirut comprising urbanists, designers and filmmakers.

The Origins, Use and Tensions of Regional Categories

The Arab category as used by these scholarly initiatives achieves two important and practical objectives. First, it serves as a useful temporary stage that allows us to describe the exclusion of an Arab region in academic structures of knowledge, contest the status-quo, and argue for its inclusion as a valid source of theoretical insight. Second, it provides some practical geographic delineation for institutions, to target under-researched contexts and under-resourced academics, as well as provide focused logistical, financial and technical support to establish spaces for knowledge production. In this section, I develop these two objectives further, but I will argue that the Arab category becomes unhelpful for urban scholars attempting the articulation and inclusion of local knowledge beyond these two uses.

The first utility of an Arab category is that it allows us to flag a structural problem. In one sense, an Arab category allows us to acknowledge the exclusion of the Arab region in the structuring of global urban knowledge and argue for its inclusion. Using these categories, Arab theorists, much like their Southern counterparts, confront Northern epistemology based on political aims and carrying a postcolonial connotation. Such moments of contestation can be captured in the Cairo’s school aim to move beyond “rigid categories of the past” 5 , the Beirut’s School “commitment to decolonial pedagogy” 6 and the Arab Council’s thirst for “a kind of decolonial knowledge […] that does not limit itself to responding to what is written in Paris, Berlin, Oxford, or New York”. 7 The latter also argues that “Arab social scientists have not been able to participate fully in regional or global knowledge networks”. 8 In this form, the Arab category, like the ‘Global South’, serves as a momentary platform to show how a certain region has been previously excluded from global urban theory.

The second use of the Arab category is a practical one which entails bringing together a knowledge infrastructure to logistically focus on the geographic area. As developed by the ACSS, social sciences have never been more important for the region, 9 and the Arab category has been used to delineate a safe space for scholarship from the region to emerge; resulting in what the ACSS labels as an “Arab research space”. This includes providing structural aid to extend research opportunities, establishing a scientific community that engages in high quality knowledge production, empowering researchers and protecting their interests, extending financial and educational support, and developing alternative platforms to publish and disseminate knowledge.

Beyond these two uses, the continued attachment of an Arab category to urban knowledge becomes counterproductive. I argue that grouping very diverse experiences under an ‘Arab’ regional umbrella and treating them collectively may unwittingly risk re-perpetuating the reductive generalizations which this kind of scholarship was created to contest. Therein exists a tension. What is usefully generalizable across the Arab region? An Arab label obscures the difference of cities and hinders the requirement to clearly articulate their diverse and complex urban experiences. Urban landscapes in the region may share current experiences of armed conflict, political instability, economic turmoil, autocratic governance and widespread grassroots social mobilization. Nevertheless, they vastly differ. When Arab scholarly initiatives repeatedly position themselves as regional entities and aspire to speak for the region, 10 they pose essential questions, for example: “what would it mean to speak of an ‘Arab’ security studies, and what might this include or exclude as a conceptual framework?” 11 One must then examine what is specific about the region. How is an ‘Arab’ urbanism or any ‘Arab’ scholarship different? What justifies the category?

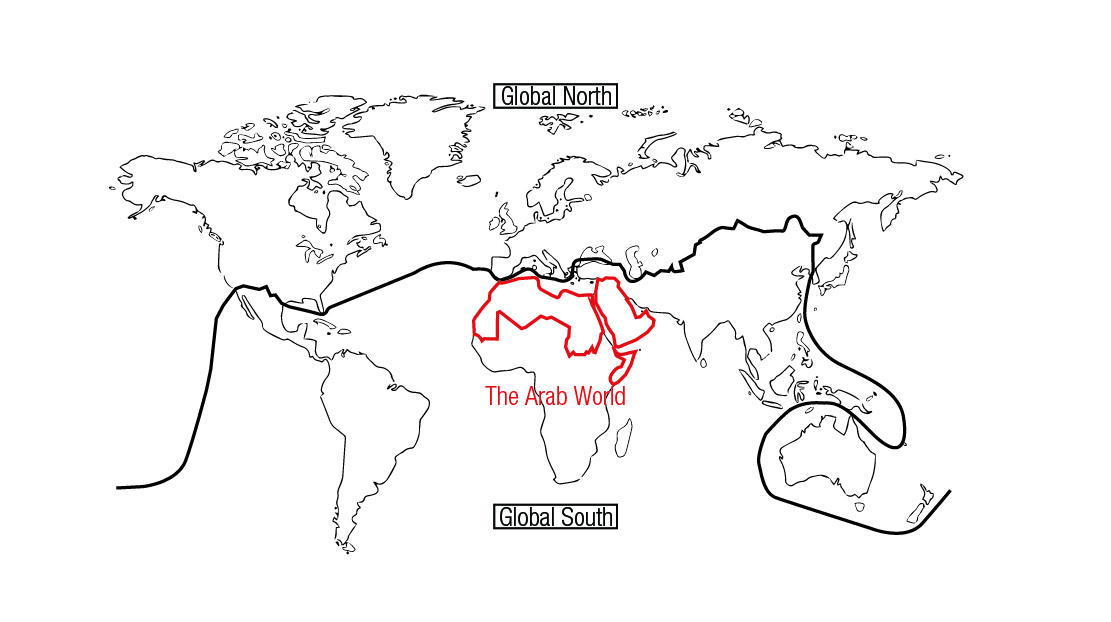

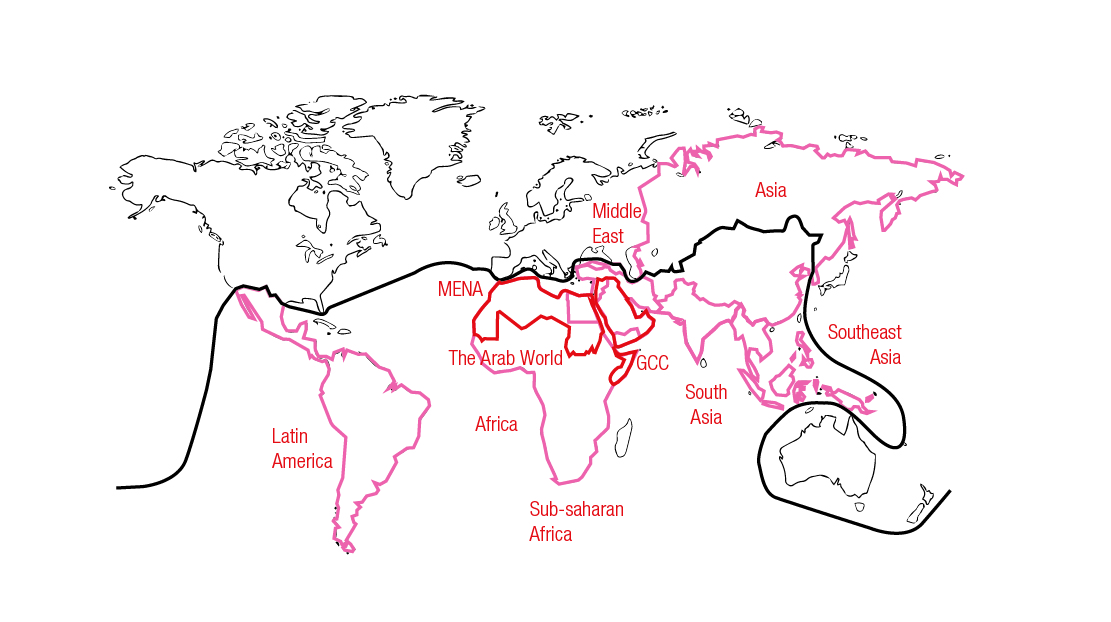

Categories such as the ‘Arab world’, the ‘Middle East’ and indeed today’s modern nation states are recently constructed geopolitical categories. The modern Arab World primarily emerged in the mid-20th century with the exit of colonial powers in the region, after which it was artificially divided into newly formed nation-states and national identities. At the same time, to form these new national identities, nation-states often violently excluded, oppressed and marginalized many minorities including Nubians, Kurds, Berbers and others. These recent geopolitical divisions, often ambiguous and dynamic, represented a biased worldview, which serves the interests of different powerful groups, and reflects shifting political and economic interests. For instance, as defined by the Arab League of Nations, the borders of the Arab world are restructured as interests in the region shift 12 , such as Syria’s recent suspended membership. 13

Some claim that the Arab region has a shared cultural-literary identity which precedes modern geopolitical categories. This shared cultural identity, however, had fluid boundaries which continually changed with the rise and fall of empires, inclusion of non-Arab ethnic groups, and external influences on the region. A clear delineation of an ‘Arab world’ hardly existed. Yet, there is certainly a long history of knowledge production from and about the region in the Arabic language which created a collective cultural identity. But even if one accepts this fluid and inclusive cultural-literary identity as the definition of an ‘Arab’ category, an ‘Arab’ scholarship remains too vague and generic to actually define. Beyond commonalities such as a shared language, culture and geographic proximity, what does this Arab identity actually include or stand for in practical terms that are methodologically useful when doing urban research?

A similar pattern can be seen in the work of urban scholars that territorialize their work from the Global South. But to avoid the risk of reductive generalization and existing geopolitical connotations of the term, the ‘South’ is not understood as a fixed geographic location, but instead reconceptualized as an abstract analytical tool that centres local complexity in previously excluded contexts. The category, however, becomes too fluid and ambiguous, and does not really mean anything. For instance, Simone ironically describes the Global South category as an “anything-what-so-ever […] detached from having a specific geopolitical history or location”. 14 However, even when the ‘South’ category is not analytically useful, many scholars continue to use it to territorialize their findings because it carries a certain postcolonial spirit of challenge and simply achieves a political objective.

Another potential analytical justification for maintaining a regional focus is that it allows us to account for and understand flows of money, goods, people and ideas that extend beyond a specific locality. At this scale of analysis, one can move beyond the limits of seeing a city or a nation-state in isolation, and instead address important regional connections, process and alliances. For instance, some scholars critique how Yemen was typically seen as distinct from ‘the Gulf’ region and reductively studied in isolation. 15 Hence, as scholarship moves away from methodological nationalism to a regional scale of analysis, a proclivity for a transnational and interdisciplinary scholarship emerges across the region. While this transnational scholarship is indeed useful, its scope should be open-ended – not bound to an Arab region. Global processes tackled in urban scholarship such as globalization or neoliberalization create flows that are impacting and connecting urban environments everywhere. Beyond Arab-Arab connections, many Arab localities are also influenced, for example, by South-Asian migrant labour or American economic and political intervention. In fact, a regional scope could obstruct the recognition of connections that occur between Arab cities and other cities worldwide. It could also maintain an unhelpful segregation of Arab cities and limits the possibility of discerning transnational processes, migrations and capital flows globally. 16 Moreover, these same global forces can manifest in very diverse and particular contextual ways within the same ‘Arab region’. The purpose of critical scholarship is to articulate these differences clearly and not to reductively group them into generic regions.

A Critical and Contextual Arab Urban Scholarship

Nonetheless, despite the tensions of regional categories, there still remains a need for contextual urban research. Under the umbrella of an emerging Arab School of thought, scholarly efforts have been producing valuable urban scholarship, and more usefully pointing to what this Arab scholarship actually stands for in practice. These initiatives converge at the aim of being both critical and contextually embedded, with the objective to decentre parochial northern knowledge and inform public action to improve local conditions. The following section analyses these initiatives outlining their objectives and values showing how they collectively stand against simplistic understandings of the region.

Often, urban and scholarly initiatives are triggered by crucial and often surprising events. As significant events unfold, scholars realize that practices of theorizing the region are insufficient and ill-equipped to both predict and reflect on local challenges. For example, in the 1990s, urban scholars of Cairo were alerted by the sudden perceived autonomy of civil society and its ability to mobilize following the 1992 earthquake in Cairo. Later, in 2005, the group consolidated and eventually formed the Cairo School of Urban Studies, after witnessing further movements of political resistance calling for social justice in Cairo. Both cases emphasized the existence of overlooked socio-political dynamics in the city and a need to better explain the urban milieu in relation to these processes. Similarly, in 2006, the Israeli assault on Lebanon pushed several individuals and initiatives to urgently map and analyse social and urban change, which has led to the Beirut Urban Lab. Likewise, the outbreak of the 2011 Arab uprisings forced many institutions, including the ACSS and Tadamun, to rethink traditional ways of understanding and representing the realities of the region.

Given their multiple motivations, roles and institutional and operational setups, the specific outputs of each group vary widely as well. While the ACSS invests in sustainably setting up an ‘Arab research space’, 17 which facilitates training, mentorship, networking, funding and publishing opportunities for Arab researchers; 18 the ASI primarily focuses on systematically producing knowledge through its publishing house, peer-reviewed journal, online magazine, audio journal or film collective. 19 While both these institutions address wider themes like environmental sustainability, social justice and gender equality, working groups tend to have a more defined focus. For instance, the Beirut School of Critical Security Studies produces publications and runs summer institutes specifically surrounding questions of security and insecurity in the Arab region. In parallel, the Cairo School of Urban Studies produced two edited volumes specifically examining how social and political forces manifest in Cairo’s urban space. Finally, Tadamun, the Beirut Urban Lab and Public Works Studio aim to equitably empower citizens to shape alternative participatory urban strategies and policies. On the one hand, Tadamun is a sustainably funded research entity regularly producing publications, articles, visuals and other open-source resources; the Beirut Urban Lab is similarly based at a university and is able to consistently produce and disseminate impactful knowledge and engage multiple publics on relevant urban issues. On the other, Public Works Studio is sustained only by balancing professional commissioned work and creative self-initiated and collaborative projects.

Despite the wide variability in their contributions, all the initiatives claim to be critical and contextual. In fact, being “critical” is interestingly the most widely recurring and emphasized keyword across mission statements. Being critical here entails contesting and interrogating taken-for-granted generalizations about the region: northern-centric visions, reductive readings within mainstream politics and totalizing meta-narratives. Instead, they call for a theory that is contextual, which includes being placed-based and people-oriented to generate accurate ideas, analysis and insights that are embedded in their surroundings. As such, these initiatives work to reveal nuance, ambiguity, messiness, diversity and complexity in order to articulate typically overlooked communities, agencies, subjectivities, and mobilizations, especially within cities. Also, in order to bypass traditional disciplinary boundaries and limiting scopes of analysis, these contributions are often committed to multi-disciplinary research and are more experimental in their methods. As a result, this contextual approach offers new ways of understanding and representing, allowing for new possibilities of knowledge to emerge.

This type of critical contextual scholarship, in turn, serves two purposes. The first is an outward-looking aim to decolonize knowledge. In fact, several initiatives explicitly embed their work in a tradition of postcolonial thought. By articulating evidence-based alternatives to hegemonic agendas, they gradually disrupt an unequal structuring of knowledge that excludes southern regions such as the Arab World. 20 To do so, they strive to remain financially independent, often relying on voluntary work or non-binding external funding sources. At the same time, they also acknowledge that the equal inclusion of Arab city experiences in academic scholarship is an ambitious goal in itself, 21 and its hypothetical achievement would not holistically resolve unequal political and economic power structures.

The other purpose for a critical contextual scholarship is an inward-looking and localized aim to be engaged in society, drive activism and achieve public benefit. Researchers often use participatory tools in fieldwork that are embedded in real urban space and street level contestation to represent and hear overlooked communities. More importantly, these scholarly initiatives aim to be transparent, making their raw data publicly accessible and understandable and often striving to improve its dissemination. Furthermore, they commit to producing bi-lingual work rather than being confined to the English language. These are liberating pedagogies as they open avenues for a more transparent and informed public debate to ensue. This knowledge can also then proliferate to networks of residents, professionals, social actors, grassroot initiatives, decision-makers and international organizations; and perhaps eventually influencing mainstream urban practices or policies. Overall, this engaged, justice-oriented and democratic knowledge has potential not only to respond to immediate conditions, but inform how we imagine the future of cities. Smaller grassroots initiatives working closely with communities tend to serve this purpose more directly in comparison to larger initiatives. For instance, in Beirut, Public Works Studio remains involved in participatory mapping or advocacy projects with marginalized communities. Likewise, academics in the Beirut Urban Lab are committed to activism towards just and inclusive cities, choosing to break out of academic circles, hold public presentations, write in local press and push for policy change.

As these initiatives grow in vibrancy, they collectively and gradually shape an Arab school of thought. Overall, what binds these differentiated efforts is a commitment to be critical of reductive generalizations, contextually embedded in a specific place in order to produce knowledge that not only de-territorializes the centrality of Northern epistemology, but is also engaged in improving local conditions. However, it is important in the following concluding thoughts to reflect on how emerging initiatives, like Arab Urbanism, inhabit a very tricky space where unjustified categories can become a liability overloaded with and inviting further generalizations.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Epistemological Debate

Using an Arab category creates space for Arab research to emerge and rescue differentiated experiences and voices in the region from academic knowledge exclusion. Yet, paradoxically, maintaining categories risks perpetuating generalizations, reinforcing geopolitical hierarchy and generating obscurity; thereby defeating the very purpose of a critical scholarship. As such, I have argued that categorizing Arab scholarship as distinct undermines its validity and obstructs opportunities for open-ended inclusion in global knowledge exchange; one which is comparative and draws connections without seeing reductive categories. 22

In fact, a degree of transferability is arguably what makes theory useful. Arab initiatives cannot aim to only be locally confined; they undeniably aspire to a certain degree of useful generalization beyond a specific context. With generalisation, scholarly efforts would be isolated into local bubbles, without common ground for experiences to compare, contrast and inform one another. And indeed, Arab initiatives do strive for their locally-embedded concepts, theories, methods and insights to travel globally – circulating, informing and engaging in dialogue with other cities and centres of knowledge. For example, the ACSS stands for theory that is embedded in its surroundings but that is nonetheless, “linked to global knowledge”. 23 Similarly, the Cairo School aims to link the mundane every day to global processes and flows, 24 while the Beirut Urban Lab “intervenes as an interlocutor and contributor to academic debates […] from its position in the Global South”. Clearly, Arab initiatives do not aim to be purely confined to the region and, in fact, their members, participants and collaborators are not solely Arab nor only based in Arab institutions. Yet, when they label themselves as Arab, they highlight the tension between regional segregations and open-ended global exchange of knowledge.

Overall, both the local specificity and the global generalizability of differentiated Arab experiences seems to be ill-served by a rigid regional category. A critical Arab school of thought, and indeed initiatives like Arab Urbanism, is consequently caught in this web of tension. These tensions around an ‘Arab’ urban scholarship, which the essay has aimed to explore, must however be situated in a broader debate within urban theory and unresolved questions on the legitimacy of generalizations. When is the individual, the district, the city, the nation-state or the region relevant? At what scale of analysis can one generalize without being reductive or obscuring particularity? How can various specific local units be compared against each other? These tensions are hard to navigate and the answers are not conclusive, but vary with the nature of the discipline, the context and the object of study. At the core of navigating such tensions is the question of how the analytical tools of describing, naming and labelling can productively articulate local knowledge.

Some scholars have accepted this challenge to find potential liberation in moving past regional categories. For instance, geographer Jennifer Robinson’s non-hierarchical ‘ordinary city’ approach is one potential avenue beyond regional labels. 25 Although, sharing the aim of dislocating Northern centrality in theory and revealing global diversity, the ‘ordinary city’ approach does not use regional categories as a point of reference. Instead, Robinson calls to unconditionally foreground the specificity, diversity and complexity of all cities while clearing inherited assumptions. By using a comparative approach, 26 findings from single cities are compared to each other, while resisting the formation of new assumptions or totalizing narratives about groups of cities. Perhaps under this open-ended outlook, blind to regional categories, a constructive dialogue can emerge between Arab cities among themselves, or with their Southern and Northern counterparts. The need to move beyond constructed categories is also at the heart of arguments for the ‘planetary urbanism’ treatise, which have gained traction with the advent of a global pandemic highlighting how interconnected the world is and forcing new modes of connectivity.

Nonetheless, such approaches are also an opportunity to frame the challenge of residing in an analytical void. Moving beyond binaries and categories, one breaks away from many overarching worldviews, concepts, and methods. It thus becomes harder to describe local phenomena in familiar ways and spaces for experimentation inevitably emerge. Perhaps a broader ongoing struggle for a critical scholarly effort, is a shortage in analytical tools and terminologies that can be helpful to address epistemological tensions. This scarcity in terminology is reflected in Mbembe’s assertion that “naming our time” is the prime challenge at stake, 27 as well as the need to find new vocabularies to interpret the complexity of phenomena in local contexts. 28

The platform this paper finds itself in, ‘Arab Urbanism’, has provided a valuable opportunity to interrogate the inherent tensions within the notion of an Arab critical urban scholarship. This essay has flagged important questions that the notion of an Arab Urbanism could pose. However, the wider underlying and unresolved struggle of how best to articulate local knowledge will remain at the heart of initiatives aiming to produce knowledge from marginalised contexts in the Arab world and beyond.

Author

Ibrahim Abdou is a PhD student at the Architecture Department in the University of Cambridge and a Gates Scholar. He is an architect and urban researcher interested in questions of housing provision, perception and use within the Global South and specifically in Cairo.

-

Jennifer Robinson, “Global and World Cities : A View from off the Map *,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26, no. September (2002): 531–54; Jennifer Robinson, “Postcolonialising Geography: Tactics and Pitfalls,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 24, no. 3 (2003): 273–89; Raewyn W. Connell, Southern Theory: Social Science and the Global Dynamics of Knowledge (Polity Press, 2007); Jean Comaroff and John L Comaroff, “Theory from the South : Or , How Euro-America Is Evolving Toward Africa,” Anthropological Forum 22, no. 2 (2012): 113–31, https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.694169. ↩

-

Timothy Mitchell, Colonising Egypt (University of California Press, 1988); Jack G. Shaheen, Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People (Olive Branch Press, 2001); Edward W. Said, Orientalism, 1995th ed. (Penguin, 1978); Seteney Shami, “Lecture: Seeing the World: How US Universities Make Knowledge in a Global Era” (AbuDhabi: NYUAD Institute, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CampYY8rpoc; Jadaliyya, “About Us,” accessed October 2, 2019, https://www.jadaliyya.com/AboutUs; Samer Abboud et al., “Towards a Beirut School of Critical Security Studies,” Critical Studies on Security 6, no. 3 (2018): 273–95, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21624887.2018.1522174; Diane Singerman and Paul Amar, “Introduction : Contesting Myths, Critiquing Cosmopolitanism, and Creating the New Cairo School of Urban Studies,” in Cairo Cosmopolitan: Politics, Culture, And Urban Space in the Globalized Middle East, ed. Diane Singerman and Paul Amar (Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, 2006). ↩

-

Throughout the essay, descriptions of these initiatives are informed by their vision statements and documents. ↩

-

The chosen list of initiatives is not exhaustive, but rather indicative for the purposes of this essay. The initiatives introduced were selected pragmatically based on the author’s personal experiences and online information was readily accessible. ↩

-

Singerman and Amar, “Introduction : Contesting Myths, Critiquing Cosmopolitanism, and Creating the New Cairo School of Urban Studies.” ↩

-

Abboud et al., “Towards a Beirut School of Critical Security Studies.” ↩

-

Mohammed Bamyeh, “Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees,” The Arab council for Social Sciences, accessed October 3, 2019, http://www.theacss.org/pages/letters-from-leadership. ↩

-

The Arab Council for Social Sciences, “ACSS 2020 Five-Year Strategy,” 2016, http://www.theacss.org/uploads/ACSS-FiveYearStrategy-ENG.pdf. ↩

-

Seteney Shami, “Message from the Director-General,” The Arab council for Social Sciences, n.d., http://www.theacss.org/pages/letters-from-leadership. ↩

-

While entities like the ACSS, the ASI and the two working groups explicitly name and position themselves as Arab, smaller initiatives are less direct. Tadamun and Public Works Studio do not overtly position themselves as ‘Arab’. However, they do belong to a circuit of smaller initiatives which carry the same ethos of critically contesting reductive understandings of the region and they collectively create a foundation that works reciprocally with bigger structural ‘Arab’ entities. ↩

-

Abboud et al., “Towards a Beirut School of Critical Security Studies.” ↩

-

“Historical Overview,” League of Arab States, n.d., http://www.lasportal.org/ar/aboutlas/Pages/HistoricalOverView.aspx. ↩

-

Bethan McKernan and Martin Chulov, “Arab League Set to Readmit Syria Eight Years after Expulsion,” The Guardian, December 26, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/dec/26/arab-league-set-to-readmit-syria-eight-years-after-expulsion. ↩

-

AbdouMaliq Simone, “The Ambiguities of Detachment: Multiple Trajectories of Urban Living in Jakarta,” Cities of the South, Cities of the North (Berlin: ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry, 2015), https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/cities-south-cities-north/. ↩

-

Nathalie Peutz, “Theorizing the Arabian Peninsula Roundtable: Perspectives from the Margins of Arabia,” Jadaliyya, 2013, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/28474. ↩

-

Powell, RC, I Klinke, T Jazeel, P Daley, N Kamata, H Heffernan, A Swain, F McConnell, A Barry, and R Phillips. 2016. “Interventions in the Political Geographies of ‘Area.’” Political Geography 57: 94–104 as quoted in Howell, “From Area to Area: The Changing Face of Area Studies.” ↩

-

The Arab Council for Social Sciences, “The ACSS Research Space,” n.d., http://www.theacss.org/pages/research-space. ↩

-

Bamyeh, “Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees”; Shami, “Message from the Director-General.” ↩

-

Arab Studies Institute, “About,” n.d., http://www.arabstudiesinstitute.org/en/pages/about. ↩

-

Bamyeh, “Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees”; Singerman and Amar, “Introduction : Contesting Myths, Critiquing Cosmopolitanism, and Creating the New Cairo School of Urban Studies”; Abboud et al., “Towards a Beirut School of Critical Security Studies.” ↩

-

Shami, “Lecture: Seeing the World: How US Universities Make Knowledge in a Global Era.” ↩

-

Shami, “Lecture: Seeing the World: How US Universities Make Knowledge in a Global Era.” ↩

-

Bamyeh, “Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees.” ↩

-

Singerman and Amar, “Introduction : Contesting Myths, Critiquing Cosmopolitanism, and Creating the New Cairo School of Urban Studies,” 27. ↩

-

Robinson, Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. ↩

-

Robinson, “Cities in a World of Cities: The Comparative Gesture”; Jennifer Robinson, “New Geographies of Theorizing the Urban Putting Comparison to Work for Global Urban Studies,” in The Routledge Handbook on Cities of the Global South, ed. Sue Parnell and S Oldfield (Routledge, 2014), 57–70. ↩

-

Achille Mbembe, “Time on the Move,” ERRANS, in Time Lecture Series 2016-17 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Institute for Cultural Inquiry, 2017). ↩

-

Neil Brenner and Christian Schmid, “Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban?,” City 19, no. 2–3 (2015): 160, https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712; Edgar Pieterse, “Grasping the Unknowable: Coming to Grips with African Urbanisms,” Social Dynamics 37, no. 1 (2011): 6.